Theme 4

Shared and competing rights

When data is about multiple people, they might not all agree with how that data should be used. Sometimes people might feel comfortable with someone else transferring data about them. In other situations, people might want to limit the types of data about them that can be moved, or the purpose of its use.

We developed two prototypes and tested them with people to explore these challenges. The prototypes aimed to provoke conversation, rather than provide some answers to the challenges of shared and competing rights:

Prototype

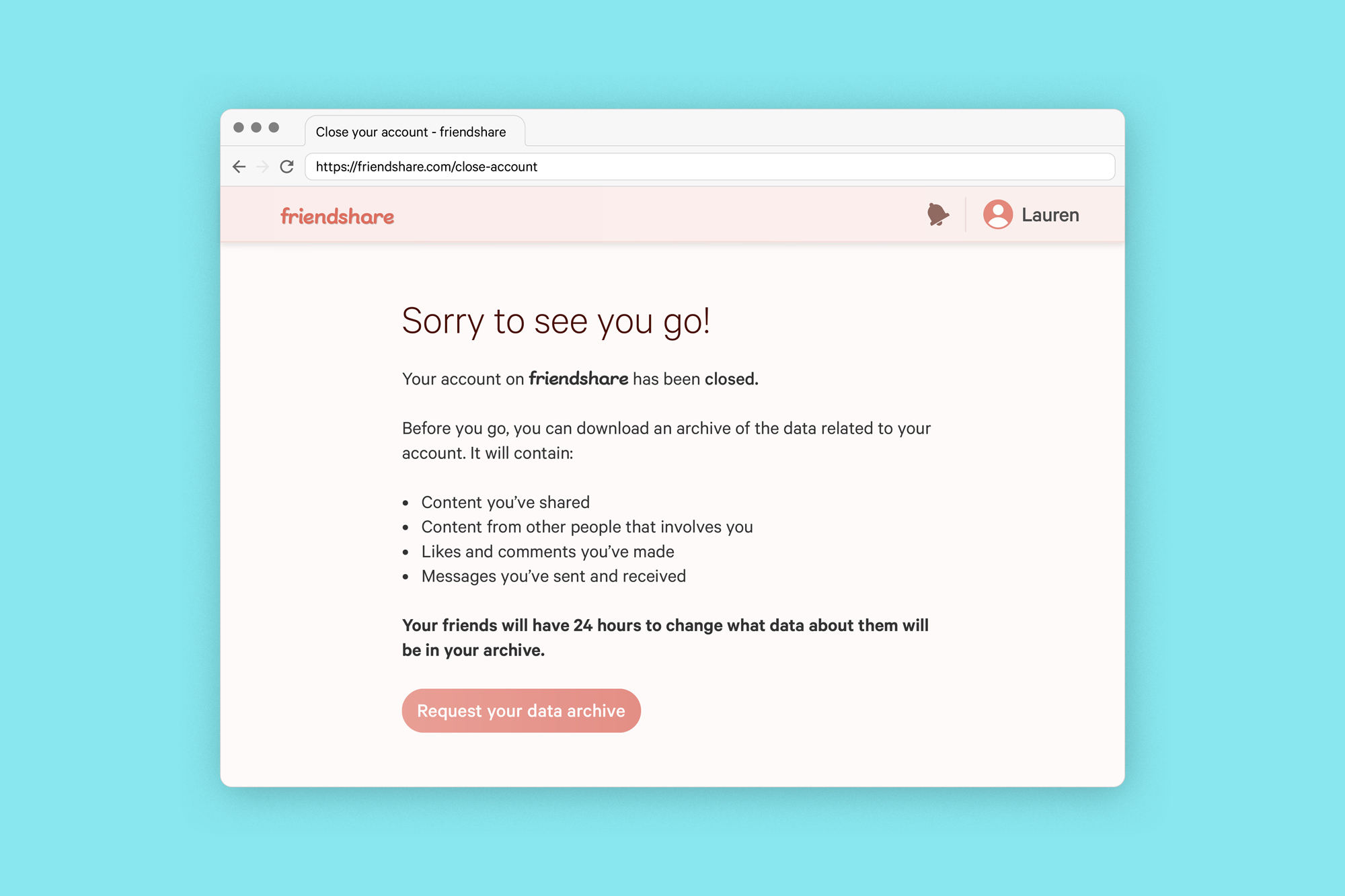

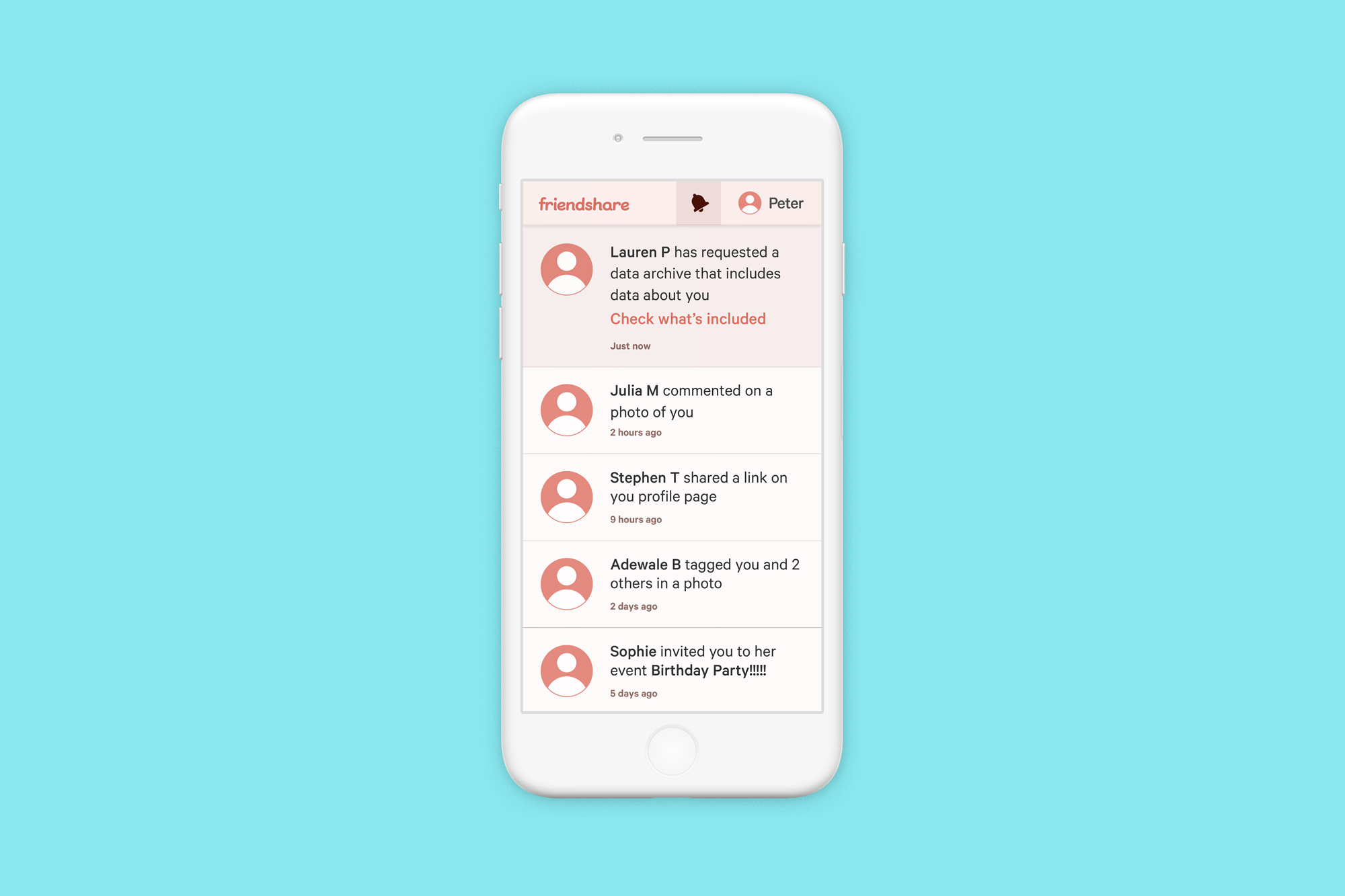

Withholding information from a social media archive

When leaving FriendShare, you can request an archive of all the content and interactions from your time using the service.

People who have data about them in the requested archive will receive a notification.

They can choose what information about them will be included in the archive.

Prototype

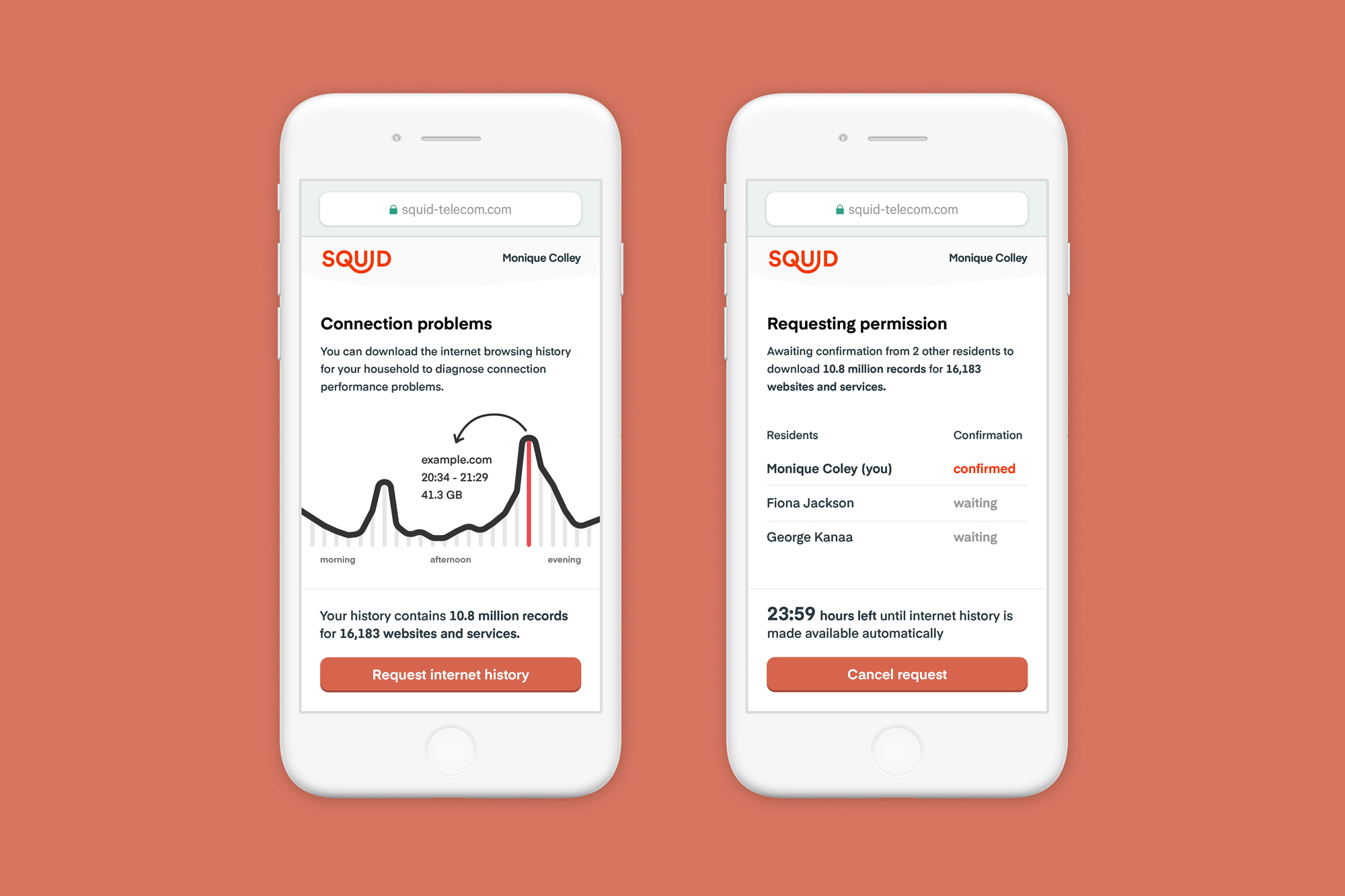

Understanding your house internet history

Squid allows you to download your home’s internet history. This helps you better understand your internet use, identify reasons for connection issues or see what data we store about you.

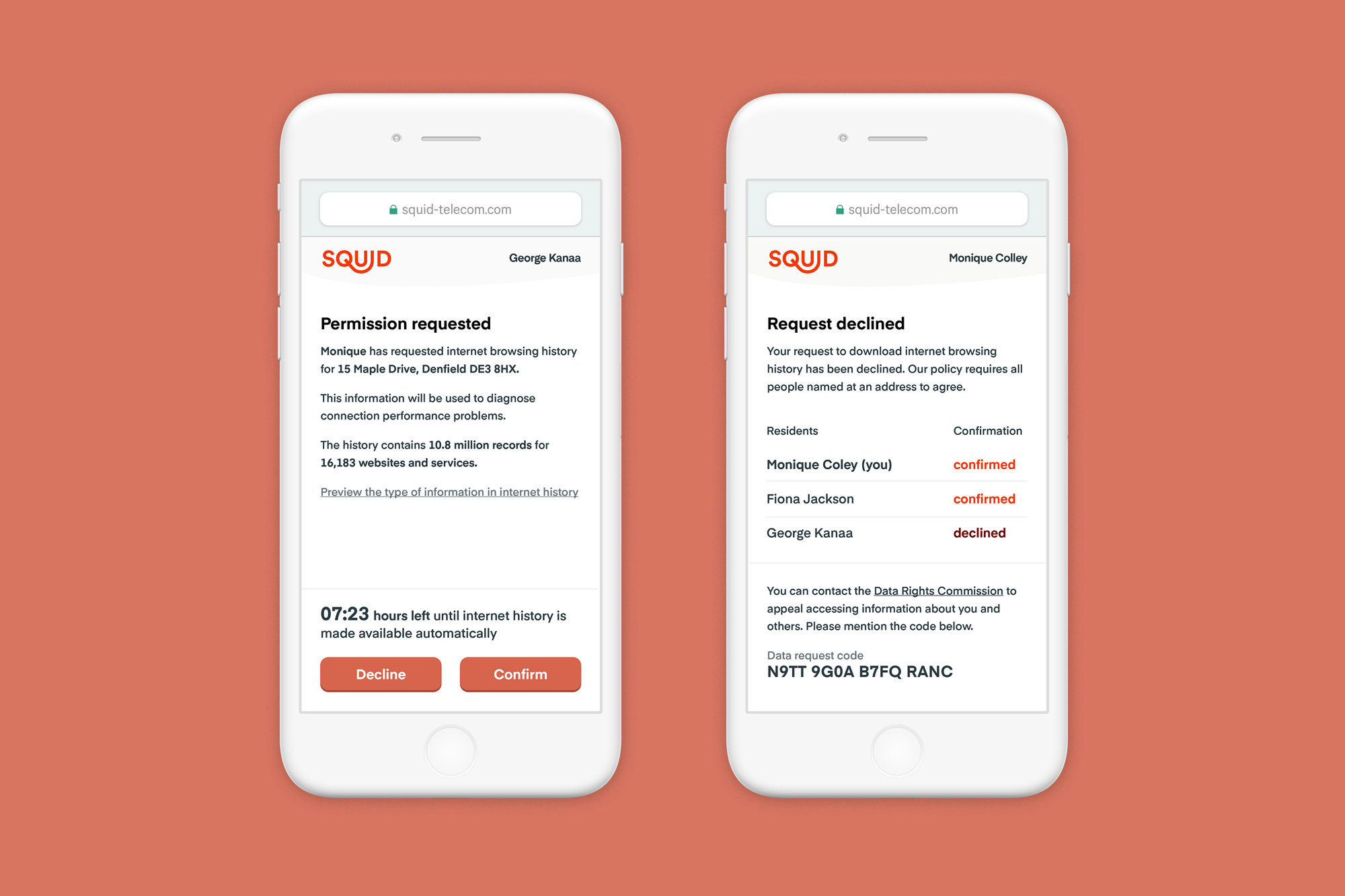

Internet history is sensitive information and can only be viewed with consent from everyone. It’s our policy that every person registered to your address agrees before this information is made available to use.

In the event that there isn’t agreement to view the house internet history, you can appeal using the mediation service.

Summary of findings

These findings describe the understanding and behaviours of the people we spoke to:

People want to be considered when someone is transferring data about them

This relies on people knowing that data about them is being transferred, understanding their rights around data portability and having a clear way to exercise these rights. For example, people were very positive about the idea of being alerted to someone else transferring data about them from a social network. However, in reality, this may be impractical.

People can be described in data held by services they’ve never used

Whether through family shopping lists, photos on social media or voices on smart speakers, data can describe people who have never consciously used a service. How does someone’s right to data portability work in a situation like this, and what is their ability to contest someone else's rights?

People sometimes have competing individual rights

One person’s right to data portability could compete with another person’s right to delete that same data. For example, housemates might disagree about how their internet browsing history is used. In this example, one person’s right to data portability is in direct competition with another person’s right to privacy.

GDPR, Data Portability and Data About Multiple PeopleContents

GDPR, Data Portability and Data About Multiple PeopleContents